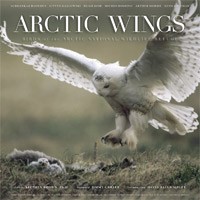

The following is an excerpt from an essay by retired wildlife biologist Fran Mauer, first published in Arctic Wings: Birds of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (Mountaineers Books, 2006).

Okiotak, or “One Who Remains in Winter,” is the Inupiaq name for the Gyrfalcon. This large falcon is found primarily in the northern tundra and mountains of the Arctic Refuge, where it preys largely on ptarmigan during the winter and small mammals, ptarmigan, and other birds during the summer. Individuals of both color phases--gray in varying degrees of intensity and white--occur in the Arctic Refuge. Although most Gyrfalcon remain in the Arctic year round, some individuals are known to move as far south as central South Dakota during winter.

Resident Gyrfalcon breed and nest earlier than the migratory birds of prey that come to the refuge. This gives the Gyrfalcon first pick of the prime cliff-nesting habitats. Like other species of predators, Gyrfalcon populations rise and fall in response to ptarmigan population cycles. Because these birds are resident in the Arctic and are at the top of the food chain, monitoring of their populations may help to track accumulation of contaminants in the Arctic environment.

The Peregrine Falcon, perhaps the best known of the falcon species, nests in the Arctic Refuge on river bluffs and rock outcrops on the south side of the Brooks Range, and from the northern margin to the mountains to the Arctic coast. The peregrines that nest in the northern part of the refuge are referred to as the Arctic Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus tundrius), and the peregrines that nest south fo the Brooks Range are known as the American Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus anatum).

Olaus Murie was the first to band young Peregrine Falcons in what is now part of the ARctic Refuge. He did so in the summer of 1926 while travelling with his wife, Margaret; their one-year-old son, Martin; and Jesse Rust, up the Porcupine River on their way to Old Crow Flats, where they also banded flightless geese. At that time they found “duck hawks”--a common name for peregrines at the time--to be common along the canyon cliffs of the Porcupine River. Thirty years later, Olaus and Margaret would lead an expedition to the Sheenjek River, which began a campaign to establish the Arctic National Wildlife Range, a 1960 precursor to the Arctic Refuge.

Peregrine Falcon populations throughout North America declined to dangerously low levels in the 1960s. The cause of the decline, it was later learned, was the accumulation of pesticide metabolites, especially from DDT, in the fat tissue of Peregrine Falcons. High levels of these pesticides resulted in thinning of peregrine eggshells and consequently much lower reproductive success. Eventually the Peregrine Falcon was placed on the endangered species list. Much of the credit for saving the Peregrine Falcon from extinction, and many other species for that matter, goes to a true heroine of our times, Rachel Carson. She detected scattered shreds of evidence that pointed to the negative influences of pesticides and other chemical pollutants in our environment. Rachel, a writer and editor for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, labored with the data collection for several years before finally drawing public attention to the problem in 1062 with her now-classic book, Silent Spring. It was through Carson’s courageous determination to publish her findings and defend the evidence she compiled against critics from the chemical industry that made the difference. Responding to an alarmed public, Congress finally passed a law in the early 1970s banning DDT and some other dangerous pesticides from use in the United States.

Peregrine Falcon populations remained at very low levels for several years following the pesticide ban. Populations along the Porcupine River of the refuge began to show signs of increasing in the early 1980s. On the north side of the mountains, peregrine numbers did not increase until the 1990s. When I began conducting annual Peregrine Falcon surveys on the Porcupine River in 1988, the number of pairs had just increased to sixteen pairs with thirty-eight young, up from a low of six pairs and thirteen young in 1976. During the next five years the number of pairs more than doubled, to thirty-three.

On the north side of the refuge, peregrine numbers were extremely low. In the mid-1980s, only a few pairs were found during extensive surveys. Their numbers began to slowly increase, and by the mid-1990s there were at least twelve pairs present. One of the most gratifying aspects of my work during those years was to document the recovery of a species at a time when so many others were declining around the world. IT was a thrill each time I discovered a new pair of peregrines occupying a site where there were no previous records. I remember wishing that Rachel Carson could share in the excitement of finding each new pair. Unfortunately, Rachel died before the peregrines began to increase. The recovery of North America’s Peregrine Falcon populations is, however, a fitting confirmation of her heroic efforts.

The original purpose for establishing the Arctic Refuge was to protect for all time this rich, diverse, wild place, where natural processes have continued unaltered by modern humans since the beginning of time. Or, as Olaus Murie once said, it is “a little portion of our planet left alone.” Will the white Gyrfalcon continue to hunt the snow-white ptarmigan in the wild whiteness of winter? Will Peregrine Falcons continue to bring food, freshly plucked from the sky, for their young? Will these wild birds of prey and all of life in the Arctic Refuge be allowed to live free of disturbance and alteration of their habitats? As Margaret Murie once asked:

“Will our society, our modern society, realize the value of keeping such an area, at least, empty of technology and full of life?”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

FRAN MAUER is a retired wildlife biologist who provided resource data and analysis in support of the proposed Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), which ultimately established new national parks, wildlife refuges, wilderness areas, and wild rivers in Alaska. He worked in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge for twenty-one years, where he conducted field surveys of Peregrine Falcons and Golden Eagles, and studied interconnections between caribou and Golden Eagles on the calving grounds of the Porcupine caribou herd.