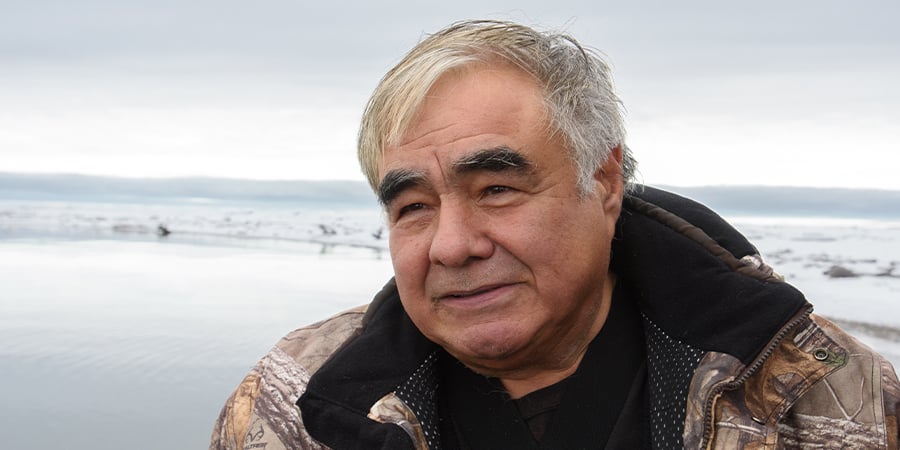

Robert Thompson is an Inupiat Eskimo wildlife guide who lives on Barter Island, beyond the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. In addition to guiding, he enjoys hunting, dog mushing, carving ivory, and wood crafts. He is also an excellent camp cook and a storyteller of local history. Thompson has been invited to speak across the nation about the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. This is an essay “Cultural Reflections” originally published in the book Arctic Wings: Birds of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (Mountaineers Books, 2006).

Sometimes we hear the Snow Buntings—what we call snowbirds—before we see them. The snowbird’s arrival in Kaktovik signals the first day of spring. After a long winter they are so welcome; this species is one of the few songbirds of the Arctic. To hear a snowbird singing perched upon your canvas-wall tent when you wake up adds much cheer to your day. To hear the song of the snowbird from inside your house as it comes down through the kinguk—the ventilation system—is an uplifting experience.

I live on the end of the Arctic Ocean on Barter Island, within the boundaries of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. There are 300 residents in my village of Kaktovik; I believe it is the most remote village in the United States. Birds have a significant place in the culture of the Inupiat, my people. Birds are a source of food, to be sure, by other aspects of their existence bring us joy as well.

A group of Herring Gulls flying over the ice sheet of the Chuckchi Sea. Alaskan Arctic.

Shortly after the snowbirds return, we anticipate the return of the various birds we hunt. The winters here are long and at times very severe. Outside activities are reduced because of the short days and extreme weather conditions. With the arrival of the geese, people come alive, and there is a flurry of activity as people prepare to go to the spring hunting camps. This is an event that we look forward to all winter. It is a time for the renewal of cultural activities. Camping and hunting are family affairs, and young people are introduced to this part of our culture, which brings families together.

Hunting is an activity that we have depended on for our existence for thousands of years. It is part of what defines us as a people. In these modern times, much of our culture has changed. Hunting activities are a part of our culture that holds our community together.

When a young person makes his first catch of each animal or bird, traditionally it is taken to an elder, who praises the young person and lets the youngster know how important he or she is to the community. In this way our culture continues and self-esteem is reinforced. As the first catch happens in the spring hunting camp, it is a happy occasion.

A ptarmigan in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

The birds of winter add much to the winter scene. The land can be so quiet without them. They are not many in species but they are truly remarkable. The raven has to be the toughest bird in the world. When we go out after winter storms, he is there to greet us. I think he is like us; he truly loves this land, as he could surely choose to fly to a less-harsh land. And to see ptarmigan in the hundreds of thousands in the willow patches makes the land feel full of life. Later, in May, seeing breeding pairs across the North Slope with the alpenglow of the midnight sun turning them pink as an experience to remember.

King Eider pair along the coastal lagoons and lakes of the Arctic Ocean (Western Arctic, Alaska).

The birds come from here, the Arctic, our home, because this is where they are born. In this age we are able to learn where our birds go when they leave us. I call them our birds, but they are the birds of the whole world. They go to six continents and all the states. Each bird is unique. The flight of the Arctic Tern is amazing; it flies all the way to Antarctica and back again. The American Golden-Plover migrates to Argentina, the Yellow-billed Loon to Russia, the Eastern Yellow Wagtail to Indonesia.

All is not well with our birds. Will the Eskimo Curlew return? Is it still of this earth? Can the Buff-breasted Sandpiper continue to exist with its habitat marginalized? Our birds live in places around the world during the rest of the year. Will the chemicals that pollute those areas affect us because of the birds we eat?

The habitat of our birds must be protected. The birds need this area—the Arctic Refuge—to continue their existence. They have no voice, so we must look out for them. They depend on us. We have lived with these birds for thousands of years; our culture is entwined with them. Will the quest for oil overpower their need for habitat in which to breed? In the places our birds migrate to, will those people take care of them? We must do all that we can to assure their protection.

Time goes on. Someday, I will be the elder. Perhaps a young person will bring me a bird, his first catch, and I will be so happy. Our culture will continue, perhaps for thousands of years more. We can hope.

Robert Thompson is an Inupiat Eskimo wildlife guide who lives on Barter Island, beyond the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. In addition to guiding, he enjoys hunting, dog mushing, carving ivory, and wood crafts. He is also an excellent camp cook and a storyteller of local history. Thompson has been invited to speak across the nation about the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.