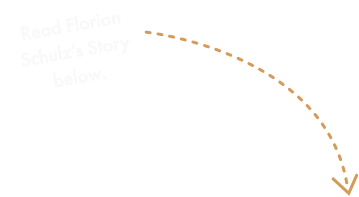

"There are beautiful mountains and forests in my homeland, as well as ancient castles over a thousand years old and ruins that date back millennia. Although magnificent in its own way, nothing in Europe matches the size or scope or connectivity of the last wild places in western North America: from vast mountain vistas to an astonishing array of interdependent wildlife, birds, forests and plants. The wilds of North America I have come to treasure above all else are not replicated anywhere in Europe. In these places, I am reminded of what we had, and have squandered in Europe. I don’t want that to happen here—especially in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

I have been obsessed and filled with wonder with the idea of wild places as long as I can remember. As a child growing up in southern Germany close to Lake Constance and the Alps, I read adventure stories of the Rocky Mountain west by Jack London that opened up possibilities, and my imagination ran as wild as the lands I longed to visit. When I turned sixteen, I traveled to America as an exchange student and headed for adventure in the Canadian Rockies. I was exhilarated, and voracious. Unable to express words powerful enough to my friends and family back home about what I was seeing and feeling, I bought a telephoto lens and began to photograph my first images of elusive wildlife. From that moment, I have been striving to tell stories of my discoveries living among the wildest places and life left on planet earth—the place I feel most alive, and where life feels most real to me.

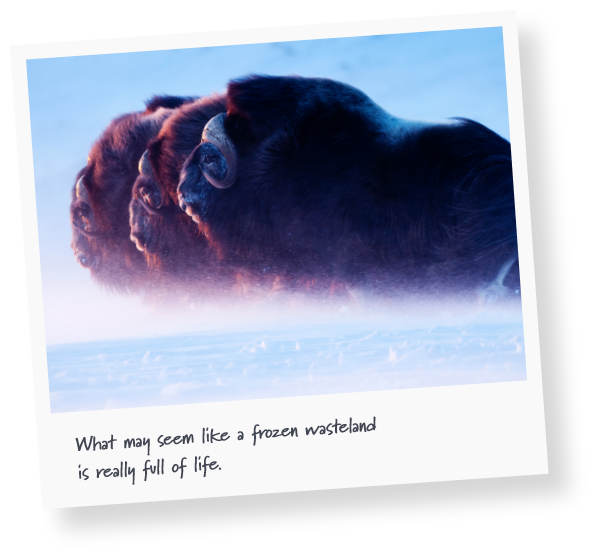

It wasn’t long before I discovered that these natural places were under threat from all kinds of ill-conceived development—from mines to be built in the headwaters of clean watersheds that are home to the largest salmon runs in the world—to clearcutting, roadbuilding, coal mining, and oil drilling development in the most biologically sensitive and unprotected lands and waters of the wildlife corridors connecting Yellowstone to Alaska’s Yukon. I met people in these communities who were fighting to sustain a way of life that had sustained them and their families, as well as the generations before them—and defined their place in the world. I learned that my photographs could help make a difference—especially when shown to people making decisions in governments who would never travel to these lands and experience the transformational power of being in a wild place, seeing grizzlies and hearing the howls of wolves, while feasting on the bounty of the rivers and lands.

Since the year 2000 grassroots conservation efforts have stopped proposals to drill in the Arctic Refuge by inundating politicians’ offices, phones, and social media and holding them accountable. Beautiful images play a role and have an impact. From books and events, as well as helping journalists tell their stories—my work is dedicated to making these remote landscapes real, and swaying decisionmakers, politicians and developers not to drill. There is great truth in these images. And now, with continuing threats there can be no rest until the coastal plain of the Arctic refuge is permanently protected as wilderness. I’ve seen the process to protect what we love works—when enough people care and decide to do something about it.”