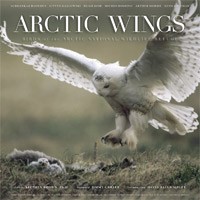

The following is an excerpt from an essay by retired wildlife biologist Fran Mauer, first published in Arctic Wings: Birds of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (Mountaineers Books, 2006).

It is in mid-March, the period of rapidly increasing daylight hours, when the first Golden Eagles arrive in the Arctic Refuge. They have recently traveled up the flanks of the great mountain chain from their winter range in the mountain states and western Great Plains, as far south as west Texas and northern Mexico. In spite of lengthening daylight, winter conditions often prevail for two more months. At first the new arrivals may rely on scavenging at sites where wolves have killed caribou, muskox, moose, or Dall sheep.

In years when Willow or Rock Ptarmigan populations are high in the region north of the mountains, or when the hare cycle is at its peak in the region south of the mountains, there is abundant food for Golden Eagles. However, in years when food is scarce during late winter, Golden Eagles have been known to prey on healthy adult caribou and Dall sheep. This is a relatively rare situation that lasts for a short period, because soon after Golden Eagles arrive, Arctic ground squirrels begin to emerge from their dens, providing a more convenient source of food.

During this time, prey abundance is critical in determining how many pairs of adult eagles will successfully breed and raise young. For example, in the canyon country of the Porcupine River at the southern end of the refuge, the number of productive Golden Eagle pairs is highest in years when the hare cycle is at its peak. In lean years when hares, ptarmigan, and ground squirrels are scarce, most pairs of adult eagles fail to produce young.

Courtship begins soon after adult Golden Eagles arrive at their traditional nest territories. This includes interactive flight displays and addition to new sticks and branches to the nest sites. Nests are located on river bluffs, precipitous rock outcrops, and mountain cliffs. Usually there are two or more nests located within a pair’s nesting territory. Use of the nests within a territory often alternates between years. Most Golden Eagle nests represent many years of use, growing in size as more branches and sticks are added during each year of use.

Egg laying seems to vary with annual changes in the timing of snowmelt. In the northern part of the refuge, Golden Eagles start laying eggs as early as late March and as late as mid-May. Only one or two eggs are laid. Since the incubation period of Golden Eagles is quite long (about forty-five days), much of this period occurs when winter conditions are still prevalent. While flying on caribou surveys over the northern mountains bordering the calving grounds, I saw adult eagles faithfully hunkered down on nests, keeping their eggs warm, with their backs dusted white with snow from swirling squalls, which are common up to early June.

When the season comes for caribou of the Porcupine herd to give birth to their traditional calving grounds on the coastal plain, an interesting association between caribou and Golden Eagles begins. During studies of calf mortality on the Porcupine herd’s calving grounds, it was discovered that predation of young calves by Golden Eagles was greater than that of either wolves of grizzly bears. Apparently eagle predation has been significant influence on caribou for a very long time. Calves will run under their mothers when they sense movements overhead in the form of a shadow. I have seen calves react in this manner when the shadow of the survey aircraft I was flying in passed over them.

As larger groups of caribou begin forming during the post-calving period in late June, greater numbers of Golden Eagles are observed in close association with the caribou. With caribou herds numbering in the tens of thousands, Golden Eagles are commonly seen scavenging on caribou that have died of causes other than predation by eagles. I once counted thirteen eagles feeding on a caribou carcass in late June. With many thousands of caribou in the vicinity, the scene reminded me of images from the African grasslands, where vultures and buzzards commonly gather to feed on animal carcasses. Eagles are known to prey on calves as late as the third week in July, when the calves weigh as much as forty-five pounds.

Nearly all of the Golden Eagles that were observed near caribou during the calving and post-calving period were subadults. Since adult eagles occupy nest sites located in the mountains south of the calving grounds at this time, they are less able to travel out into the coastal plain where the caribou are. The subadult segment of the eagle population, on the other hand, is not tied to the nest territories and is free to travel more widely to exploit seasonally abundant prey such as caribou calves, and to scavenge on adult caribou that die of other causes.

If calving caribou of the Porcupine herd were displaced from their traditional calving grounds on the coastal plain due to the oil drilling and production activities (as portions of the Central ARctic herd have been displaced by oilfields elsewhere on the North Slope of Alaska), then predation of young calves by Golden Eagles would be greater because the displaced caribou would be in closer proximity to the nesting adults and yet still be vulnerable to the aubadult eagles as well.

The undisturbed condition of the Arctic Refuge has allowed us to learn something of how the natural world works, and how the ancient relationships between species and their environment have developed over eons of time. The lives of the eagles, hawks, and falcons of the refuge are only part of the splendid tapestry of life found here. And there is still much more to learn if we are willing.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

FRAN MAUER is a retired wildlife biologist who provided resource data and analysis in support of the proposed Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), which ultimately established new national parks, wildlife refuges, wilderness areas, and wild rivers in Alaska. He worked in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge for twenty-one years, where he conducted field surveys of Peregrine Falcons and Golden Eagles, and studied interconnections between caribou and Golden Eagles on the calving grounds of the Porcupine caribou herd.