The coastal plain along the Southern Beaufort Sea in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is one of the world’s most extreme environments. The average winter temperature is -67 degrees Fahrenheit, and the land is covered in a frozen blanket for up to nine months straight.

Yet, every spring, the snow retreats. As the ice and snow melt, they reveal hardy plants like lichens and rich soils that soon fill with grasses and flowers. This green landscape is the summer home of the Porcupine Caribou Herd. The more than 200,000 caribou in the herd migrate as much as 650 miles one-way (or more than 1,000 kilometers) to feast on these summer plants. That’s like walking from San Diego, California to Salt Lake City, Utah every spring. These caribou follow the same routes year after year, and have worn hard trails across the land like roads leading them to their summer grazing spots.

The herd will encounter many obstacles like heavy snow, mountain passes, and river crossings. But these animals are built to survive in the harsh conditions of the Arctic. They have unique characteristics that allow them to overcome these challenges. Their hooves are split into four “toes” that spread out, acting like snowshoes. The hairs between these toes are wiry, and prevent snow from sticking to the bottoms of their feet. Even with these traits, the journey to their summer range is the most difficult part of the herd’s yearly migration. The full migration covers over 1,300 miles (2,000 kilometers), and is the longest land migration of any animal on earth. The herd is believed to have been making this migration for the last two million years.

Many caribou in the herd are pregnant during the migration, and the expectant mothers are eager to arrive on the coastal plain. The herd starts their migration just in time to give birth in the safety of the coastal tundra. There, the young caribou have the best chance of survival. With the promise of nutrient-rich grazing and healthy calves just ahead, the migrating herd presses on through the difficult journey.

Their mothers are well fed on a rich diet of grasses and lichen, so they produce large amounts of fatty milk. This milk helps the caribou calves to double in size in just ten days. Young caribou put their rapidly growing legs to use, and explore their new world with wobbly steps. They also quickly adapt to eating plants, and are fully weaned before they have to make their first migration away from the coast in early autumn. As the cold temperatures return and the growing season comes to a close, the herd begins the long journey back. The mothers and calves travel across the coastal plain, over the mountains, and to their winter home in the inland forests of Alaska and Canada.

The development of gas and oil infrastructure has blocked some of their paths to the birthing grounds. The herd is forced to make new trails, putting them at greater risk of predation from wolves, bears and golden eagles. They are also challenged by changing climate, which causes unpredictable snow cover and extreme swings in temperature. This weather can block their paths through mountain passes and kill the new plants that should be waiting for them on the coastal plain. You can help protect their summer home and protect the future of this unique Arctic species.

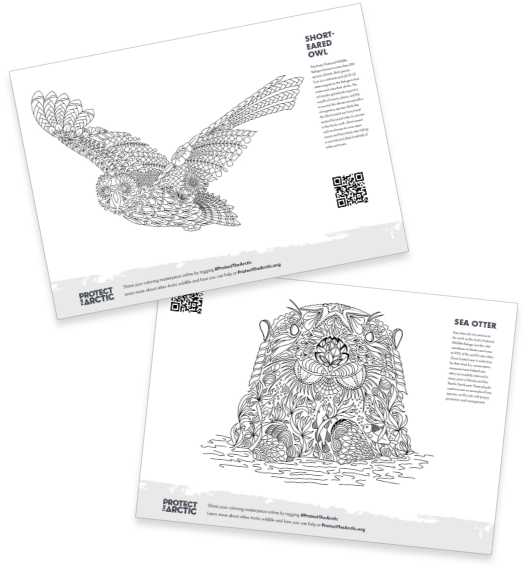

Download our pack of 6 Arctic animals to color and share. Polar Bear, Arctic Fox, Caribou, Peregrine Falcon, Short-Eared Owl, or Sea Otter… Which is your favorite?